Varna Sutra : Patra, Pushpam - Kanjivaram's Flora

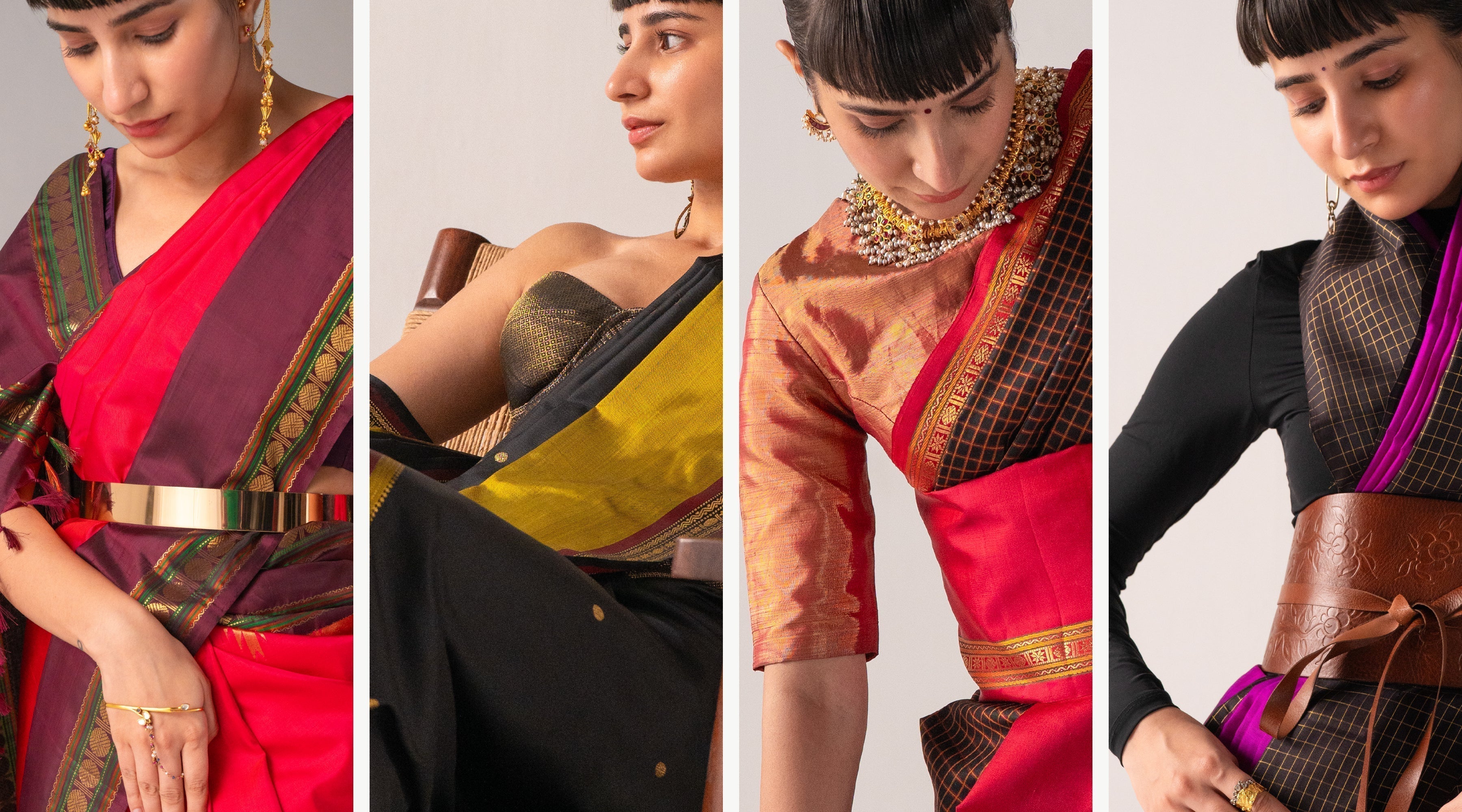

Motifs offer a new dimension to the visual appeal of a traditional sari, upholding a unique form of creative expression within the craft. Plant and floral motifs have held a place of importance in textile designs since ancient times—painted, printed and woven, drawing inspiration from the richness of the natural environment. In Varna Sutra's Patra Pushpam, we turn to the intricacy and rich legacy of plant and flower motifs on the kanjivaram.

KANJIVARAM’S FLORA

Over the past 500 years, silks from Kanchipuram have formed a fundamental part of the cultural tradition of the South Indian world. The sheer beauty of the silks of the South, with jewel toned colours enriched with threads of gold—the zarigai pattu—has been recognised the world over. When one looks at Tanjore paintings, temple murals and portraits of the royals, it is clear how weavers have adopted temple art into weaving patterns in textiles.

There are striking differences in the way motifs are woven into sari designs in different parts of India. Kanjivaram weavers have drawn from symbolic patterns to derive meaningful motifs that suit their traditional weaving methods. They bring them to life with the eye and hand of an artist, visible in a variety of motifs woven in supplementary warp or weft threads along the borders and enhancing the pallu. These designs are usually small and repetitive, inspired by nature, items of jewellery or everyday objects, and fit well into the overall format. They occasionally adorn the body of the sari as buttas or buttis, depicting a floating design element.

The remarkable motifs inspired by the architecture of a thousand temples and the natural environment of Kanchipuram are seen in some of the most recognised woven patterns of manga, gopuram, rudraksham and kamalam. Trees and plants have always played an important part in the myths and customs of India. Many parts of a tree, including its flowers, seeds, and sometimes even its wood or bark, are considered holy, and associated with gods, planets and months, among other things.

A traditional textile like the kanjivaram conveys a great deal to a discerning eye, not only about the artisan’s skill, but also about the roots and inspirations of its designs.

Discover the breadth of expression and artistry of the Patra–Pushpam (plant and floral) motifs of a kanjivaram -

KAMALAM OR THAMARAI (LOTUS)

Inset: Fine kamalam buttas in zari dot this sari body.

The pundarika or lotus has been regarded in India as a manifestation of the divine, and associated with the goddess of wealth Lakshmi, Saraswathi and also with Brahma, the creator. Unlike the lotus motif in Varanasi brocades, in Kanchipuram it is adapted as a kamalam—a small, but stylised eight-petal floral motif which invokes the goddess of wealth. Like Indian classical music, a sari’s design is always governed by a certain language of form and layout, retaining the weaver’s individual expression—something that is perfectly illustrated in the interpretation of the lotus motif.

GODHUMAI (WHEAT)

Inset: The godhumai motif appears here woven diagonally in gold zari on the border.

Wheat, the golden grain, is called godhumai in Tamil, and has been a staple in India since ancient times. While South India is synonymous with rice-growing, wheat remains an essential commodity in the region, used as a base for several dishes. Wheat is a universal symbol of fertility and abundance. On the kanjivaram, godhumai or wheat kernels are represented as small buds that come together in a delicate geometric form on the border or pallu of the sari. This fine design detail might be woven in coloured silken yarn or in rich zari, adding a shimmer to the silk.

VAZHAIPOO (BANANA BLOSSOMS)

Inset: Vazhaipoo stripes run down the entire breadth of this bridal kanjivaram, stopping at the korvai borders

In South India, every part of a plantain tree is used, from the fruit, stem and flower, which are eaten, to the leaf on which food is eaten, and which is woven as fibre into various objects. The purple vazhaipoo or banana blossoms are as delicious as they are beautiful, used as an ingredient in several dishes in South India. Banana flowers are interpreted within the bold language of the kanjivaram as horizontal stripes or lines of alternating colours running through the body of a sari, a design termed aathi vazhai in Tamil. Fine zari might embellish these linear patterns, emphasising the geometric beauty of this element.

KODI VISIRI (CREEPER)

Inset: The kodi visiri border runs along the pallu of this kanjivaram; the undulating design in sharp contrast to the neighbouring geometrics

These floral creeper designs elegantly link motifs and buttis on the kanjivaram. One can see a resemblance between the floral patterns on the sari and those adorning South Indian temple lintels. The term kodi visiri in Tamil aptly describes the gentleness of this design, and the way the tendrils cling and wind themselves around trees. On the kanjivaram, the creeper fans out along the borders or is woven as a pattern on the pallu. The styles are unique, and they are precisely and intricately represented on the drape. One can see how the shape and size of the kodi visiri motifs synchronise beautifully with the overall design of the sari and its symbolism.

MALLI MOGGU (JASMINE BUD)

Inset: Delicate, slim zari malli moggu motifs dot the body of this kanjivaram, interspersed among the definition of the checks

Mokku or moggu is the Tamil word for a flower bud. The jathi malligai is a part of everyday ritual—adorning a woman’s hair, forming garlands for gods and bridal couples. Malligai poo or jasmine is the single most used flower in Tamil Nadu, and these delicate long buds are always represented as buttas on the body of a kanjivaram. Referred to as ‘rain drops’, these were traditional designs which made the art of weaving truly original, drawing on local culture.

KASA KASA KATTAM (POPPY SEED CHECKS)

Inset: Tiny kasa kasa checks fill the body of this kanjivaram; further amplified by the bold korvai border contrast

The tiny white poppy seed, known as kasa kasa in Tamil, is used as an ingredient that adds texture and creaminess to traditional dishes. Poppy seeds are also known to have a host of health benefits, while the plant has beautiful flowers in shades of pink and red. The kasa-kasa checks on the kanjivaram are exquisite and delicate—so fine that their detail is visible only when the sari is draped. Woven in multiple colours or with rich zari, the tiny checks are dazzling and radiant in their beauty.

PANAI MARAM (PALMYRA)

Inset: The interlocked paai madi features on the pallu, in a section of gold zari, instantly recognisable as a stylised basket weave

As we have seen, traditional weavers frequently derive inspiration from nature and their immediate environments—from animals, birds, creepers and leaves, to flowers, foliage, fruits and seeds, and sometimes even from ancient crafts like basket weaving. The weave referred to as paai madi is a panoramic view of the tabby weave in basketry. Panai maram or the Palmyra tree is native to Tamil Nadu, and the leaves of the tree are used to make baskets, fans and other objects. The thick stalk of the leaf is cut into strips and used to weave baskets. The basic structure of the weave in a kottan (the traditional Chettinadu basket) is called the gundumani weave—the basic one up-one down plain weave. In this weave, the warp and weft are aligned so that they form a simple criss-cross pattern. The ability to plait fibres together is not new to Tamil Nadu. The fine silk mats called pattu paai of Pattamadai in Tirunelveli district are incredibly intricate and made of a special kind of grass called korai. We also see the basket weave in cotton lungis, referred to as payyadi lungis, which were once exported to Southeast Asian countries. The paai madi weave in a kanjivaram usually forms part of the ground fabric of a sari, playing with colour and contrast, and is sometimes depicted richly in zari in the pallu.

PULIYAM KOTTAI KATTAM (TAMARIND SEED CHECKS)

Inset: Bold puliyam kotttai checks fill the body of this kanjivaram

The tamarind fruit and its seeds play a role in our everyday lives, rooted in South Indian culture. The seeds are used while playing ‘pallankuzhi’, which is a famous traditional board game in Tamil Nadu. Tamarind pulp is the basic ingredient for several South Indian delicacies including sambar, rasam and vatha kuzhambu. The two-toned sari with checks the size of tamarind seeds (puliyam kottai)—about an inch or less in size—patterned all over the body has an enduring charm. With checks in various combinations of colours, this sari, traditional to Tamil Nadu, has a distinct identity.

RUDRAKSHAM (RUDRA'S TEARS)

Inset: The rudraksha motif runs along the border of this kanjivaram in zari, framed by geometric vanki borders

The Skanda Purana mentions that rudrakasham beads originated from the tears that Shiva shed when the tripurars were destroyed. Tripurars were devotees of Shiva, but because of their atrocities, Shiva had to destroy them. According to mythology, when Parvati wanted to adorn herself with jewels, Shiva reached up and rudraksha fruits fell from heaven into his hands by the dozen. These she wore as earrings, necklaces and bangles. The commonly held belief is that the beads dispel the evil eye and avert misfortune. Rudraksha beads are considered sacred by the followers of Shaivism, and are worn during meditation and also used as japa-malas (rosaries). Rudra is the Vedic name of Siva and aksha means tears. This motif looks striking when woven along the border of a sari as an accompaniment to the main thematic design, or as bigger buttis woven on the body. This design element is another example of how weavers assimilated attributes from the physical environment and from mythology, contributing to the unique identity of regional weaving traditions observed today.

MANGA (MANGO)

Inset: Tiny jacquard manga motifs fill the body of this kanjivaram, executed in tonal silk yarn

The manga or mango motif is ubiquitous in a kanjivaram, as well as other craft traditions around India. This motif illustrates how even the simplest shape can be put together in an extraordinary way with varied contrasts with the clever use of indigenous weaving techniques. The Sthala Vruksham is the mango tree of the Ekambareswarar temple, the main Shaivate shrine in Kanchipuram. One can still see the fossil of a 3,500-year-old mango tree in the temple premises, whose four branches are said to have yielded four different types of mangoes. The mango motif is a perennial favourite of craftsmen all over India. In kanjivarams, it is woven in different sizes; not just on the border and mundhanai but also as small buttas dotting the body. The motif is referred to as kalga and ambi in northern India, and the iconic paisley internationally. A legendary design, used as prints and for embroidery, the motif was a part of the Persian repertoire, made famous by Mughal art and fostered in the Kani shawls of Kashmir. The mangoes of South Indian sari designs are stockier and more stylised, while the Kashmiri version and the paisley have longer curves retaining their characteristic shape.

THUTHIRIPOO (INDIAN MALLOW)

Inset: Tiny and delicate, the thuthiripoo motif appears as defining bookend borders on this kanjivaram

The concept of showcasing flowers is inspired by common sources of art, but their visual interpretation in the kanjivaram tradition stands out. Garlands of flower petals referred to as arumbu, lavangapoo, madhulam (pomegranate), and sampangi (champaka) give fluidity to designs on the borders. The Indian mallow is a beautiful tropical flower common in Tamil Nadu. The motif is inspired by floral garlands and showers of petals that mark special occasions. Thuthiripoo is also colloquial form of the word utharippu meaning scattered flowers, and this motif is used in between border compositions, lending delicacy and elegance to the drape.

THAZHAMPOO REKU (KEWRA FLOWER)

Inset: An exaggerated jacquard depiction of the thazhampoo reku motif forms the dramatic border of this kanjivaram

The temple motif has remained a distinct part of the design vocabulary of Dravidian and Deccani weavers since ancient times. The Dravidian style places importance on the towering gateways of South Indian gopurams. The handloom tradition has imbibed this design, its meaning and value. The rows of large triangles, interlocked in korvai, resemble temple gopurams and are referred to as reku (a sheaf of grass) or mottu (flower buds) in the case of smaller triangles. Indian culture cherishes flowers, which represent the female principle. The thazhampoo is a heavily scented yellow flower with sharp petals that grows along river banks in Tamil Nadu and is used in hair ornamentation. The temple design is interpreted as a reku in the dhotis and saris of South India, and it narrates the story of the sari as a key contributor to our identity and culture. If the reku is smaller, it is referred to as pillayar moggu.

The kanjivaram sari weaves together mythology, history and culture, rooting the textile tradition in its South Indian context, and telling stories through its motifs and symbols. The plant and floral motifs we explore in this edition of Varna Sutra are a unique tribute to the natural world. Each of these motifs, apart from its aesthetic appeal on the silken drape, also lends the sari its rich symbolism.

As we trace the origins of the Patra Pushpam motifs—from plant to weave—we are struck not only by how beautifully nature influences design, but also by the way in which the kanjivaram weave interprets nature within its own context. By juxtaposing intricately executed botanical drawings against the kanjivaram’s interpretations of them, we observe that the motif is not a literal rendition of the plant or flower, but a uniquely stylised and more elemental version, that fits seamlessly into the kanjivaram layout and embellishment. This skilful stylisation and adaptation of the motif, to stay true to the aesthetic of the craft, is a reflection of the power of design language to retain its authenticity while drawing inspiration from diverse cultural and mythological contexts.

The weaver’s sensitivity to the traditional design and grammar of the kanjivaram is evident in the artistic, beautifully abstract rendering of the natural world on the sari’s drape.

We hope you have found joy and beauty in the plant and flower motifs of the kanjivaram in Kanakavalli’s Patra Pushpam.

- Research by Sreemathy Mohan, illustrated by V.Senthilkumaran, edited by Aneesha Bangera This article was updated in July 2020.